Nonetheless, a closer examination reveals that they offer competing models of development, though they became modern nations at about the same time, India in 1947, China in 1949. They launched reforms from different starting points: China embarked on market reforms in 1979 - a decade earlier than India - from a centrally planned, economically backward, agrarian economy; India initiated its reforms in the early 1990s and is today a semi-socialist economy in a fledging democracy ridden with problems of corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency. Today, China is seen to be ahead of India; but there is much speculation on their respective growth trajectories.

What do the numbers tell us?

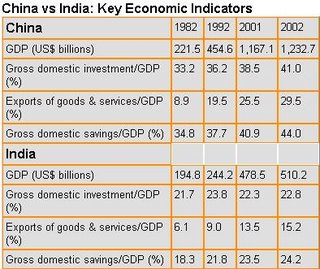

China's economic growth thus far is certainly more impressive than its South Asian cousin. China's gross domestic product (GDP) grew by an average of 9.7 percent during 1982-92, and by 9 percent during 1992-02. On the other hand, India grew by 5.6 percent and 6 percent in the same respective periods, though still impressive by most developing countries' standards. India's lagging is due to a number of reasons. The Chinese save twice as much as Indians: for every US$1 earned, the Chinese save 44 cents, compared with 24 cents by Indians. As a result, the Chinese invest more in their economy than do the Indians. The share of gross domestic investment in GDP is 41 percent in China, compared to 22.8 percent in India. The Chinese economy is also more opened to international trade, and therefore gains from greater specialization in areas where China excels. China's export share of GDP is twice that of India's.

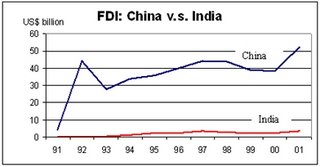

A more compelling reason to account for India's slower growth is the flows of foreign direct investment (FDI). As shown in the diagram below, the amount of FDI into India is only a small fraction of that into China. Of course, any statistics, especially those reported by communist cadres who are rewarded for economic performance of their localities, should be taken with a grain of salt. As frequently pointed out, China's FDI figures are likely to be exaggerated by "round-tripping" - domestic capital disguised as foreign investment (passed through Hong Kong) to qualify for special investment incentives reserved for foreigners. India's FDI figures, however, may be understated because they exclude foreigners' reinvested profits, the proceeds of foreign stock market listings, intra-company loans, and so forth. This may not be a simple issue of whether India is able to attract foreign investment, since it may have as much to do with New Delhi's policy or practice for years of keep foreign investors out of the country.

Foreign vs private companies

China may boast impressive records in courting foreign investors, but it has few successful indigenous private companies on which it can pride itself. China's private companies are systematically discriminated against by the capital market and the legal system. Private property rights have only recently been recognized by the central government and given legal recognition and protection. The state-owned banking system is notorious for molly-coddling the inefficient and debt-laden state-owned enterprises, while shying away from the vibrant private sector.

The stock markets are also largely reserved for those enterprises with state backing. Ironically, foreign companies in China are granted better recognition, legal protection and market access than indigenous private companies. The internationally better known Chinese firms, such as China Telecom, and the white goods, or major appliance, maker Haier, were formerly nurtured in the state cradle. China Telecom is a state-owned enterprise, and Haier was formerly a collectively owned township and village enterprise (TVE).

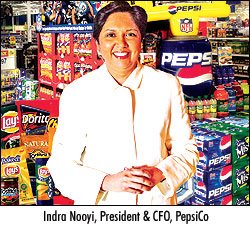

In stark contrast, India's brand of internationally well-known companies, such as software giants Infosys Technologies and Wipro, and pharmaceutical and biotech start-ups Ranbaxy and Dr Reddy's Labs, are born and bred locally. "Indeed, by relying primarily on organic growth, India is making fuller use of its resources and has chosen a path that may well deliver more sustainable progress than China's FDI-driven approach," write Huang Yasheng and Tarun Khanna, dons from the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MIT, and the Harvard Business School, in an article published in Foreign Policy in August, 2003.

"China's export-led manufacturing boom is largely a creation of foreign direct investment, which effectively serves as a substitute for domestic entrepreneurship," they argue.

The point about India's better use of resources is worth noting, as the numbers seem to lend support to this hypothesis. China's GDP growth rate (8 percent in 2002) is about double that of India (4.6 percent); however, China's savings ($542 billion) are four times higher than India's ($122 billion), not to mention that its FDI inflows are more than 10 times greater ($52 billion compared with $3.5 billion).

Not just markets - institutions matter

Why is entrepreneurship able to flourish in India but not in China? "Blossoming entrepreneurship in India is due in part to a liberalizing financial market, which provides capital access previously exclusive to certain caste groups to the budding entrepreneurs. Capital is now available to private start-ups, through venture capitalists, the banking system, and the stock markets," says Vijay Kelkar, an advisor to the Indian Ministry of Finance, at a speech recently delivered at the Australian National University in Canberra.

Aside from a financial market that allocates resources more efficiently, India seems to have in place the institutions - democracy, a functioning judiciary, property rights and so on - conducive to economic development. Huang and Khanna, from MIT and Harvard, argue: "Democracy, a tradition of entrepreneurship, and a decent legal system have given India the underpinnings necessary for free enterprise to flourish." Of the world's top 200 small-sized companies listed by Forbes in 2002, 13 were from India; while four were China's - all of them based in Hong Kong.

Nonetheless, China's greater openness to the outside world and its ability to benefit from foreign trade and investment can be attributable to a "stronger state" (albeit authoritarian), one that is able to advocate and implement policies in the country's interests, rather than being held hostage by any vested interest groups. By contrast, India's burgeoning but unruly democracy means that in order to gain power, the Indian policy makers are often trapped in myopic vested interests and are sometimes held hostage by protectionist voices.